Hola. This is Barbara again. I have three new topics for you this week that all deal with different types of cultural trauma and ways to overcome them: the neglect and oppression of Chocoan culture in the mainstream literary discourse of Colombia, Helena Urán Bidegain’s account on the Palace of Justice siege in 1985, and the recent elections in Nicaragua, which bring back memories of the Somoza dictatorship.

Writing and reading about the Chocó department

In the last years, Colombia’s Chocó department got some literary attention. This development was overdue. For many decades, the Chocó on the Pacific coast was almost excluded from the literary discourse of the country. This has changed because important writers from the metropolitan areas took up the region as a setting and topic of their novels. Pilar Quintana wrote about a childless woman who adopts an orphaned puppy in her first novel La perra (The Bitch). The protagonist lives near Buenaventura, the biggest port on Colombia’s Pacific coast and it is Quintana’s merit to capture the atmosphere of the setting very well. In 2020, Tomás González published the book El fin del Océano Pacífico (The end of the Pacific Ocean), in which he tells the story of Ignacio, a doctor who undertakes a trip to the Pacific accompanied by his family, in search of the meaning of life.

It requires high sensibility and respect to make a culture visible that is in many aspects very different from the urban cultures in Bogotá or Medellín without falling to clichés. El Chocó is Colombia’s poor house, geographically separated from almost all of the rest of the country by the Western Andes. Despite being one of the rainiest regions in the world, many villages and towns lack drinking water - a clear sign of political neglect. According to a census from 2005, 82,1 % of its population is Afrocolombian, 12.7 % are of Indigenous heritage. Since the land is rich in minerals and hyperproductive soils, it is also the territory of violent distributive struggles among various gangs. Perhaps the name of the region derives from the Aymara word «choque», which means «gold» - a fitting, however unproven, story.

Due to its remoteness and diversity not all attempts to make Chocó a literary setting fullfill the requirement to reflect this cultural richness. Velia Vidal, for example, criticises the reproduction of racial stereotypes in Lorena Salazar Masso’s recent novel Esta herida llena de peces (This wound full of fish). Velia Vidal is an author and cultural manager from the area. In Aguas de estuario (Estuary waters), an epistolary novel, she writes about her experiences upon the return to her home region. At the same time, she works for the organisation Motete in Quibdó, the capital of Chocó. Its major aim is to promote reading and raising the educational possibilities of the local youth. The region still has a comparably high rate of illiteracy (13,4 %).

Listen to this short interview, which Velia Vidal gave during her visit to the Madrid Book Fair to learn about her motivation and projects. Vidal also talks about a new travel book with the title Hoy somos río (We are river today). Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find more details about its publication, which was supposed to be available by the end of September. Maybe, you’ll find out more about this if you follow Velia Vidal or her organisation Motete on Twitter. If you have other sources, please, drop me a note so I can update the information. Thank you!

My life and the palace

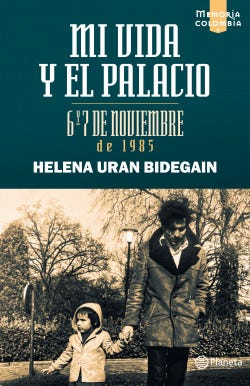

With her book Mi Vida y el Palacio (My life and the palace) Colombian writer Helena Urán Bidegain has contributed to the collective memory and the restoration of truth in her country. And with that being said, we have travelled back to Colombia’s capital Bogotá and also touch ground in Berlin.

Urán’s father, a judge, was killed in one of the most brutal acts of violence in the history of Colombia. In 1985, a terrorist group attacked the Palacio de Justicia (Palace of Justice) in Bogotá and took the Supreme Court of the country hostage. It was the terrorists’ aim to hold a trial against then president Belisario Betancur. The Colombian state launched an intensive operation to retake the building and succeeded, but at a very high cost. 98 people died in the event. Urán Bidegain was 10 years old, when her father died. She, her mother and sisters left the country.

After many stops in other countries, Helena Urán Bidegain today lives in Berlin. First, they never spoke about the tragic loss at home. When she realised that she was not alone with her pain, she started to talk about her experience as a child and started to investigate. With the help of a public prosecutor they found evidence that Helena’s father had been murdered by the military, not the terrorists. When her father’s body was exhumed, the prosecutor could prove that Mr. Urán had been tortured and executed out of court. This means that he left the Palace alive on the first day of the siege, but was later brought back into the building to make him appear dead in the siege. His daughter assumes that he was killed because he was investigating human rights violations of the military at that time and had raised concern about the strong militarisation of Colombia.

Only in 2020, 35 years after the events, Helena Urán Bidegain was able to write down the shocking truth about these events of her childhood to help her and other victims of political violence overcome this traumatic experience. It’s more than a personal story. Listen how she talks about her motivation to relive her experience through writing:

I learned about the author through a short feature in Deutschlandfunk, which got transcribed in English here.

Elections in Nicaragua

For the last topic today, we have to move North to Nicaragua. Nicaragua held general elections on November 7th 2021 to elect the President, the National Assembly, and members of the Central American parliament. The Central American parliament goes back to the Contadora group, which sought to resolve the civil wars of the 1980s in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. But let’s not digress, but return to the focal point of this election: the re-election of Daniel Ortega, who has been serving as President of Nicaragua since 2007. Previously, he was also a central figure of the Sandinista revolution who overturned the dictatorship of the Somoza family. He was also President from 1985 to 1990. Currently, his wife Rosario Murillo serves as his vice-president.

What is so special about these elections? First of all, the elections show clear signs of democratic degeneration. Opposition leaders and media voices were detained, put under house arrest or forced to leave the country early on. They had no chance to start their political campaigns. On November 7th, Ortega could still claim he won against five opposition leaders, but those are hardly known. Wikipedia’s talk page shows how much the election results are disputed. Interestingly, only the page in English is so controversial, the page in Spanish much less so. It seems that some left-leaning people from all over the world who feel the little country has been trolled and betrayed by its big neighbour in the North again, try to raise their voice and defend Ortega and his merits as a leader of a socialist revolution.

If Ortega and his ruling party had let in foreign journalists and international election observers to create transparency, they might have found it easier to be recognised as a rightfully re-elected government. Instead, Ortega and his followers claim that nobody outside of the country can really judge the fairness of the elections because there were no reporters on the ground. Jacobo García was one of the few Western journalists in Managua last week and recounts what he calls «un gran teatro». Of course, sometimes the reporting about Nicaragua is one-sided and the opposition has its own agenda, too. I am also sure the US secret service plays dirty. After all, the previous international interventions in Nicaragua make any current engagement of the U.S. and Western allies complicated.

I, for my part, still find it very hard to believe, that Daniel Ortega even tried to arrest his former comrade and vice-president Sergio Ramírez (from 1985 to 1990) who has no political ambition anymore, but is trying to bring more cultural education to his country (see Tertulia, vol. 18) and rescue democracy. Even the progressive Guardian takes sides in this dispute. It must be very hard for Ramírez to go into exile at his age after having defeated a long-time dictatorship and now seeing the old corruption return.

Secondly, I have to comment on these elections because the Sandinista revolution in 1979 was part of my pre-teen political awakening and I personally feel disappointed about the direction of the Nicaraguan democracy, i.e. the decline of what was meant to become a socially just country. I watched the Sandinistas take over control and start a huge alphabetisation campaign and big economic reforms. I dreamt about going there to help and started to learn Spanish. I have to admit, I never went. I came close to the border at the San Juan River in Costa Rica, but never crossed it. With great enthusiasm we read a biography about Augusto César Sandino (1895-1934) at Middlebury’s Summer School (I think it was in Jaime Concha’s class). Sandino founded the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, what is today Ortega’s ruling party. Already in Switzerland, I became a member of the foundation Pan y Arte and went to Ernesto Cardenal’s poetry readings. Even at a very old age he had to continue with his book tours, because he had no pension.

I am not disappointed by this development because my former romantic revolutionary self has turned conservative (maybe a little, reality has taken its toll when it comes to revolutionary beliefs 😉, «un discurso político sin saliva»). I keep on fighting for effective social justice that deserves the name, but what makes me sad it this recurring scheme of growing authoritarianism that runs across Latin America. I also received some heat on Twitter when I said that Ortega’s win had been an easy one because of muting the opposition beforehand, but was shocked about the sarcasm and whataboutism that I got as responses. I didn’t respond again to avoid further polarisation. Anyway, it is nothing international Twitter brigades can finally fix, but Nicaraguans themselves. Yet, we should not leave them alone in this situation. As Erika Guevara-Rosas, Amnesty International’s Americas Director, says:

Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo’s renewed mandate as president and vice president augurs the perpetuation of the structures behind the repressive strategy against critical voices and guaranteed impunity for crimes under international law. Moreover, this new period portends the continued forced migration of those who are criminalised for speaking out.

The international community must do more than standing by as brave Nicaraguans continue to fight for their dwindling human rights.

This is all for today. Let me know what you think and feel about these stories. Come back in two weeks to read more about culture from Latin America, Spain and wherever a variant of Spanish is spoken.