Hola. This is Barbara with cultural news from the Hispanic world. This time, I have the following recommendations for you: a podcast about the Spanish of Mexico, a conversation with Minnesotan writer Anika Fajardo, and Alain de Toledo’s fascinating testimonial about his use of Ladino and his cultural heritage. Even though we currently have to bear with certain travel restrictions, books and culture will always allow for travels in our minds.

The Spanish of the country with the largest number of native Spanish-speakers

Mexico is the country with the largest number of native Spanish speakers in the world. As of 2021, 124.85 million people in Mexico spoke Spanish with a native command of the language.

Hence, it is good to know how Mexican academic institutions attend to their speakers and their concerns. For that reason, the RNE (National Radio of Spain) program Un idioma sin fronteras went to Mexico to interview Concepción Company, deputy director of the Mexican Academy of Language and researcher at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). She is also a member of the famous Colegio de Mexico. If you have a minute, have a look at her impressive CV - it’s 68 pages long.

The 30-minute-long interview is perhaps the more convenient option to learn about Company and her passions. The podcast serves as a good intro to the sociopolitical peculiarities of the Spanish of Mexico. It spans a lot of interesting topics that do not only deal with language itself, but also with power relations. The development of the relations between the Mexican language academy and their Spanish counterparts is among these topics. During the Franco dictatorship, there was no cooperation between the relevant language institutions of the two countries at all so that Mexico independently advanced the academic organisations, which set the norms to help speakers solve their issues and doubts. Company also mentions the important regional differences in Mexico from North to South, the many contributions of Mexican indigenous languages to the global lexicon (chocolate, avocado, … for more examples, see here), the use of Spanish North of the border and the use of English and sociolinguistic phenomenona, such as the non-binary word «Latinx», South of the border.

If you wish to hear more about what she has to say, listen to the RNE podcast.

Anika Fajardo about finding family

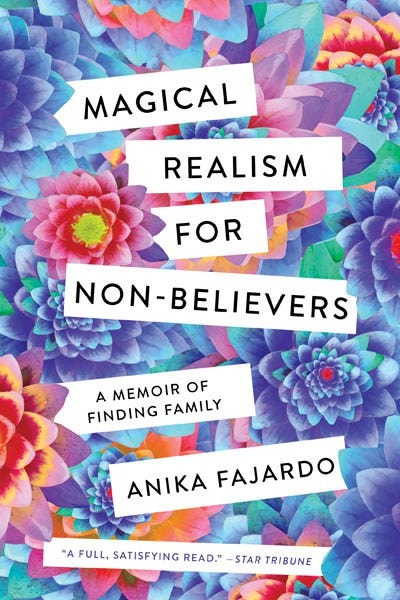

Richard McColl had Anika Fajardo on his podcast lately and I was happy to learn about her and her books. She gained fame recently because she wrote the tie-in novel aimed at middle-grade students to Disney’s latest movie Encanto Fajardo was born in Colombia, but raised in Minnesota. In 1995, she went back to Colombia and wrote about this experience in the book titled Magical Realism for Non-Believers

She reflects on what it meant for her to go back to Colombia, have families in two different countries, and how this experience infused all her later writings. Here’s a short excerpt from the Kindle version of this book containing a short conversation with a Colombian man on her first flight back:

Family to me meant my mother’s little bungalow in Minneapolis, it meant a log cabin built by my grandparents on the edge of a lake in Minnesota, it meant uncles and cousins and friends who occasionally entered my trajectory. Could it also mean strangers in Colombia? “I’m visiting my father,” I told the man, the simplest answer. “Do you visit him every Christmas?” I shook my head. “I’ve never met him before,” I said. I don’t know what I expected from this explanation, this story I had told before. The story of my not knowing my own father. Like anyone’s life history, it is both intensely personal and yet in some way, acutely universal.

It is a well-written book and is a good example of how the awareness of having a hybrid cultural identity develops. It would be nice to see a Spanish translation of the book so that more Colombian readers got a chance to learn about this side of the far-spread Colombian community.

If you wish to learn more about Fajardo’s motivation to write and publish, listen to her conversation with Richard McColl.

Alain de Toledo: a Sephardic Jew in France

As a child, Alain de Toledo thought that "Spanish" meant "Jewish". Then he realised that the Spanish he spoke at home was not the same as the one he was taught at school... It was Judeo-Spanish or Ladino as linguists call it today. In his testimony for the magazine K. he recounts what makes the use of Ladino so special to him on a personal level, but also what it means to all those who have carried this language through so many centuries to the present day.

Alain de Tolédo was born in Paris in 1947. He is a lecturer at the Paris 8 Economics University. He is the president of the association «Muestros Dezaparesidos», which aims to build a memorial to the Sephardic Jews deported from France.

The article is originally written in French, but you can switch to English on the menu selections on top of the magazine page. Here’s a short quotation from the article so you get an idea about the writing style.

… autre bizarrerie de ma vie personnelle, concerne un séjour dans la colonie de vacances avec le SKIF (Sotsyalistisher Kinder Farband), un mouvement de jeunesse affilié au Bund, au château de Corvol l’Orgueilleux. Là je découvre qu’il y a des Juifs qui ne sont pas espagnols, que je suis un petit sépharade et qu’il s’est passé des choses terribles pendant la guerre. On y célèbre les héros de la révolte du ghetto de Varsovie mais on ne parle pas trop de la déportation et je commence à comprendre pourquoi ma mère s’énerve quand elle entend parler allemand.

Translation: «… another oddity of my personal life, concerns a stay in the SKIF summer camp (Sotsyalistisher Kinder Farband), a youth movement affiliated to the Bund, at the castle of Corvol l’Orgueilleux. There I discovered that there were Jews who were not Spanish, that I was a Sephardic child and that terrible thing had happened during the war. They celebrate the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, but they do not talk too much about the deportation, and I begin to understand why my mother gets upset when she hears German.»

Thank you to Rachel Bortnick who pointed to this article on the forum Ladinokomunitá, which I introduced in my last newsletter.

One more thing

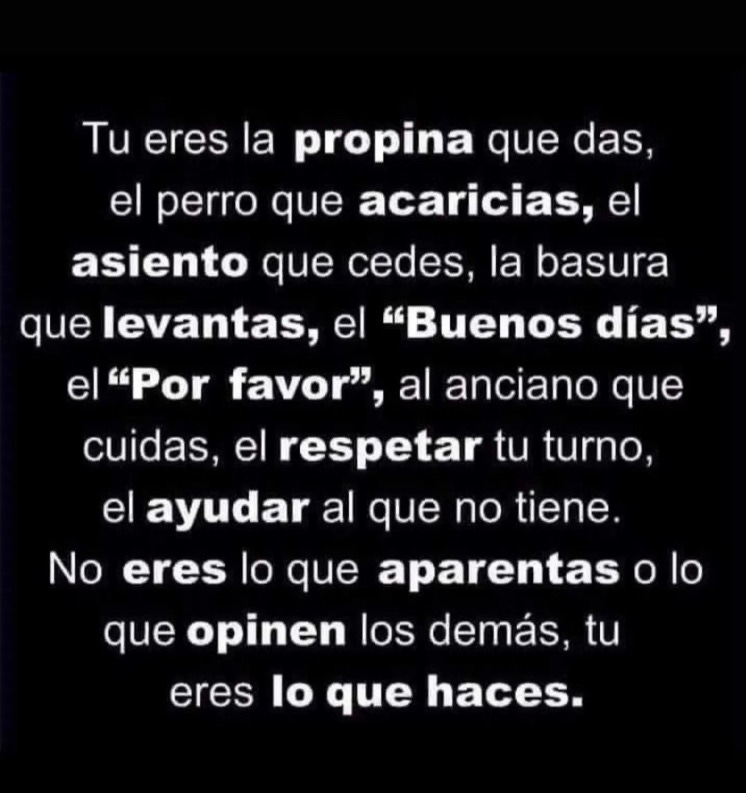

I loved this little text that reached me via a Colombian friend on WhatsApp, source unknown.

Translation: You are the tip you give, the dog you pet, the seat you give, the rubbish you pick up, the "good morning", the "please", the elderly person you look after, you waiting for your turn, you helping those who have nothing. You are not who you pretend to be or what others think of you, you are what you do.

This is all for today. I’ll be back in about two weeks with more cultural snippets from the Hispanic world.